Hear from Suzie Miller, writer of RBG: Of Many, One and Prima Facie

Trigger Warning: This article includes references to rape and sexual assault.

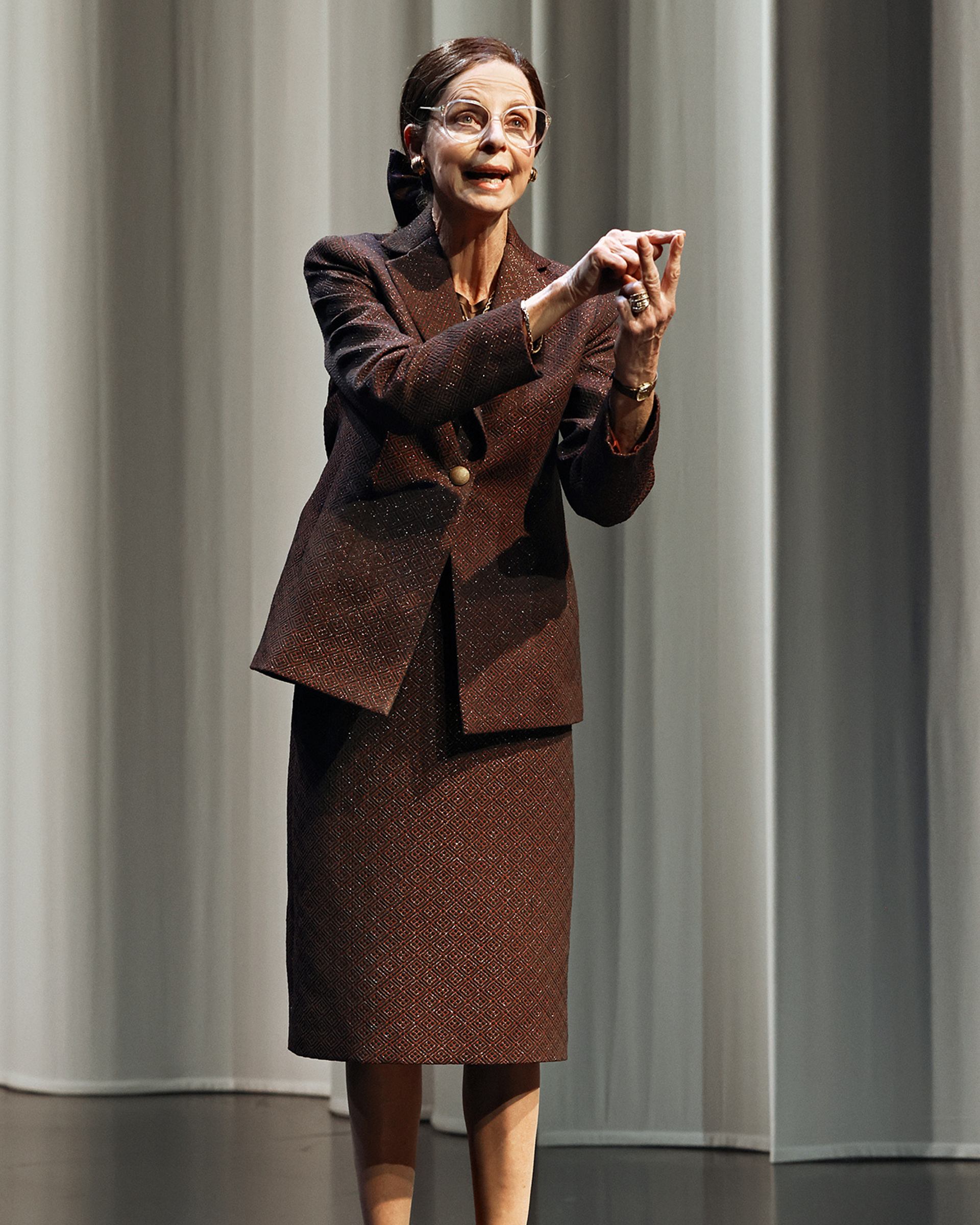

Contemporary playwright and screenwriter, Suzie Miller, is known for her exploration of complex human stories and themes of injustice.

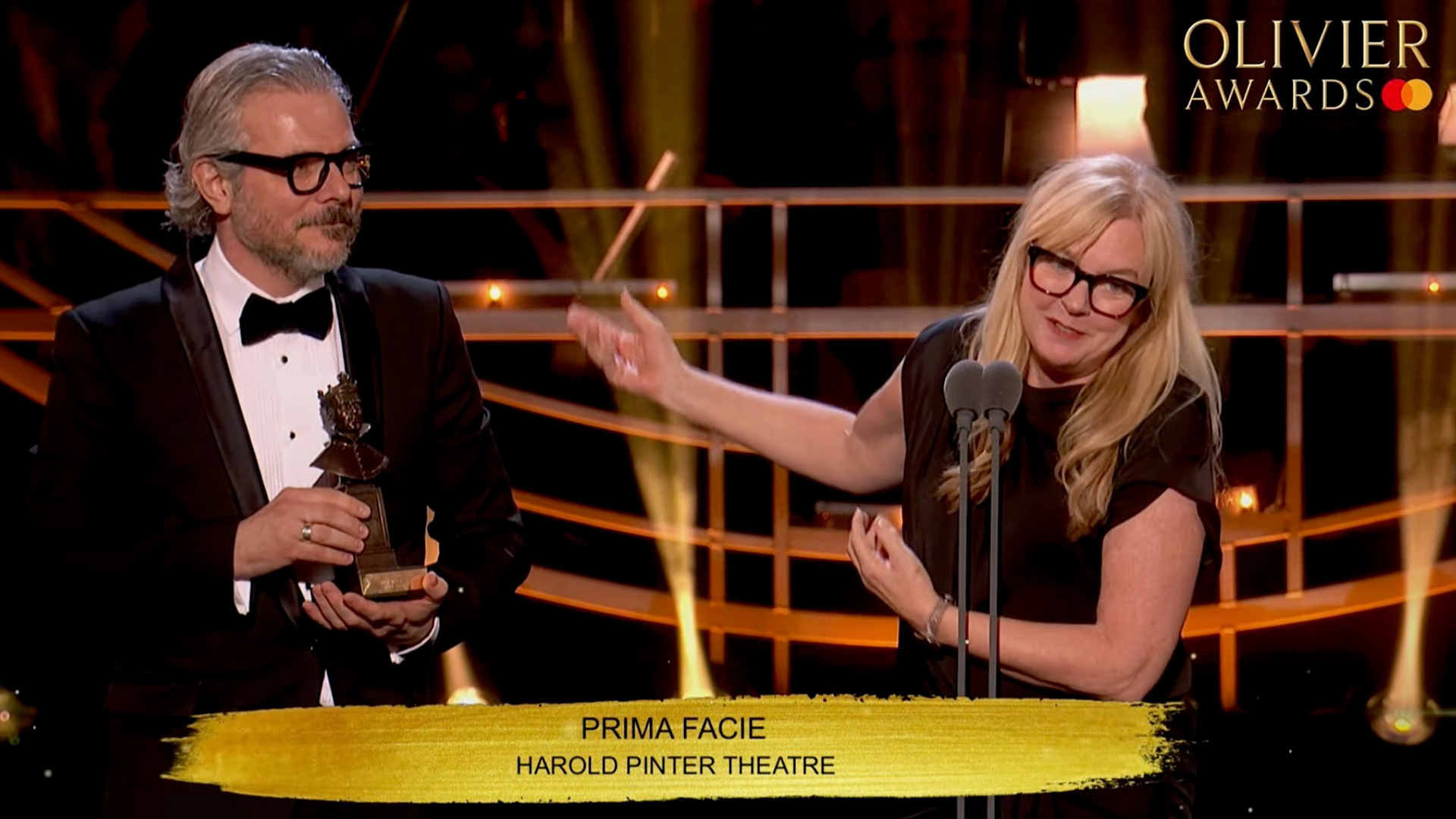

Suzie’s work is set to feature in Black Swan’s 2024 season with two of her plays, RBG: Of Many, One and Prima Facie, the latter of which achieved significant international acclaim in 2022, making its West End debut before transferring to Broadway in 2023. The production secured the Tony Award for Best Actress for Jodie Comer (Killing Eve) and the Olivier Award for Best New Play and Best Actress, in addition to other prestigious honours.

Suzie Miller in her own words:

My background has always been in the law. First, as a human rights lawyer, then a Children’s and Young People’s lawyer, and finally as a criminal lawyer where I also ran civil matters in discrimination, immigration, and victim’s compensation matters.

When I was at law school at UNSW, I remember studying criminal law and questioning how rape law seemed to be out of sync with other crimes. As a defence lawyer, I always believed that innocent until proven guilty is everything; but what I didn’t understand was how in rape and sexual assault law there was a ‘double negative’ – i.e. the prosecution needed to prove that not only did the rape occur, and then that the (usually) female complainant was not consenting, but also that the (usually) male defendant did not know that they were not consenting. There were all sorts of things done in court to complainants that just felt wrong; so many things that were back to front and that had been defined and not interrogated appropriately.

Then, when I was a practising criminal justice and human rights lawyer, one of my jobs was to take statements from young women who had been sexually assaulted and raped. Often, I was the first person their social workers took them to for the purposes of making a statement. There were hundreds and hundreds of cases, and in each of them such similarity in reporting; in the way the victim responded, managed to survive, and endure it, and yet I could count on one hand the ones who reached a conviction at court. I was shocked at the figures and at how few cases the police prosecuted. I was also devastated on behalf of my clients because their lives often fell apart in the aftermath. They were victimised again by the system or by society in general blaming them or just simply not believing them.

When I wrote Prima Facie, I knew I had to show the audience how the law works before I could show them how it doesn’t. Every lawyer always gets asked ‘how can you act for someone who you know did it?’ in criminal law. I wanted to explain through the play how lawyers are just one part of the system; they argue the best version of their client’s story and that is all. They do not decide on guilt or innocence, that is for the jury and the judge.

When the show first previewed at Griffin Theatre, it felt different to any other time I had been in the theatre. Women were weeping in the audience, and everyone leapt to their feet at the end. This occurred throughout the entire premiere season in Sydney, and then for every other touring location. It was beyond what I had expected. The reaction from audiences and reviewers was one thing, but the effect it had from the law community completely blew me away. The NSW Law Reform came to a matinee, the Governor General of NSW came with her security, the judges and law makers came in droves, politicians and women who had experienced rape and sexual assault. It was overwhelming. Then, Griffin put on one show just for women who were trained in law – we had an entire audience of women politicians, barristers, judges, solicitors, and policy makers. After the show the doors were closed, and we had a Q&A that went on for hours. It was the most incredible discussion. These were the women at the forefront, the ones who had the power to make suggestions to the senate and band together to make change. These powerful women talked about their own experiences of rape and sexual assault within the profession, their experiences of watching and participating in trials of such nature. It was mind-blowing.

Then came London.

When the play was produced in London, the London bar and judges came out in massive support. The judges of the Old Bailey all came to see it and discussed the work, barristers old and young came as did the legal profession in general. After the show, I had a call from one of the senior judges at the Old Bailey who told me that she had seen the play the night before. She was the judge who wrote the ‘directions to the jury’ that must be read at trials and she redrafted the direction for rape and sexual assault to include language from the play; to point out that just because someone does not recall the event in neat chronological detail, does not mean they are lying, and she also referred to the concept of ‘freezing’, and how it is a perfectly legitimate victim response to an assault.

“All of this was incredible. Still, it got even better.”

One judge instituted that every new judge in Northern Ireland must watch a video of the play (with Jodie Comer), before they are allowed to sit on rape and sexual assault cases!

Furthermore, 3000 police officers in North Yorkshire also watched the film and discussed the way they interview and support complainants. I have had letters from them recognising where they had made mistakes in the past and determined to do better.

The progress continued.

A group of fabulous female barristers established the TESSA project. Named after the protagonist in Prima Facie, it stands for The Examination of Serious Sexual Assault law. These women are redrafting the old legislation as an offer to the senate.

This one-woman show was having a profound effect on the law community and the theatre world on an international scale. It won every AWGIE award, and many other awards around Australia. It won various awards in the UK, was nominated for four Tony Awards - including a win for Jodie Comer as Best Actress – and was nominated for five Olivier Awards in London, of which it won Best Actress and Best Play. This was beyond my wildest dreams. Of course, I had always wished for such an award, but to stand up there in Royal Albert Hall and accept it against incredible competition, was surreal and a life changing moment.

“The awards and accolades were all a playwrights’ dream, but it was the thousands of emails, letters, and online messages that Jodie and I both received from mainly women audience members that was something I could have never expected. It completely blew our minds.”

I am so excited to have these important conversations with West Australian audiences. I am an enormous fan of Kate Champion and have admired her for so many years so I can’t wait to see what she does with Prima Facie. Right now, there are 30 productions of the play in 25 different languages around the world, and this WA version, directed by someone I admire so much, will be an incredible new Australian version from WA’s own State Theatre Company.

I am thrilled to be bringing, not one, but two of my plays to Black Swan’s stage in the 2024 Season, that showcase the power and tenacity of two remarkable women; a fictional woman with Tessa in Prima Facie, and a historical icon in RBG: Of Many, One.

When I was at law school, Ruth Bader Ginsburg was an icon of mine; a woman who was brilliant, powerful, and uncompromising in her commitment to social justice. She was changing the world step by step towards giving women an equal voice in the US. Her case arguments and judgements were incredible; she was years beyond her time. I adored her and her judgements.

RBG is not as intense of a play as Prima Facie, and often there is a feel-good moment afterwards. In fact, a male solicitor friend of mine, who is married to a female judge, gave me a fabulous analysis. RBG’s husband in the play, Marty, is based on her own husband who did more than just talk about feminism, but actively shared domestic tasks in their family. I included Marty as a template to what a good, feminist-leaning man really is. Upon viewing the show, my friend Steve said that when everyone was leaving the theatre, the women were bonding, weeping and talking about how impactful it was; while the men (usually married to these women) walked out feeling quite chuffed, thinking to themselves ‘I’m a Marty!’ This made me laugh.

To be able to present these two shows at Black Swan is to be able to hold a conversation about contemporary society, to speak to audiences and to use story to offer ideas and empathy. I see the arts as the way we develop and grow as a community and society. Artists are amongst us; they see and experience what we experience, then filter it through their art form to mirror it back to us with a different perspective.

I can’t wait to see these perspectives mirrored back to me on the Black Swan stage in 2024 and I look forward to WA audiences joining me.

Suzie Miller